ANNOUNCEMENT: I made a decision this morning whilst I sat, alone, in the darkened upper floor of the local Panera.

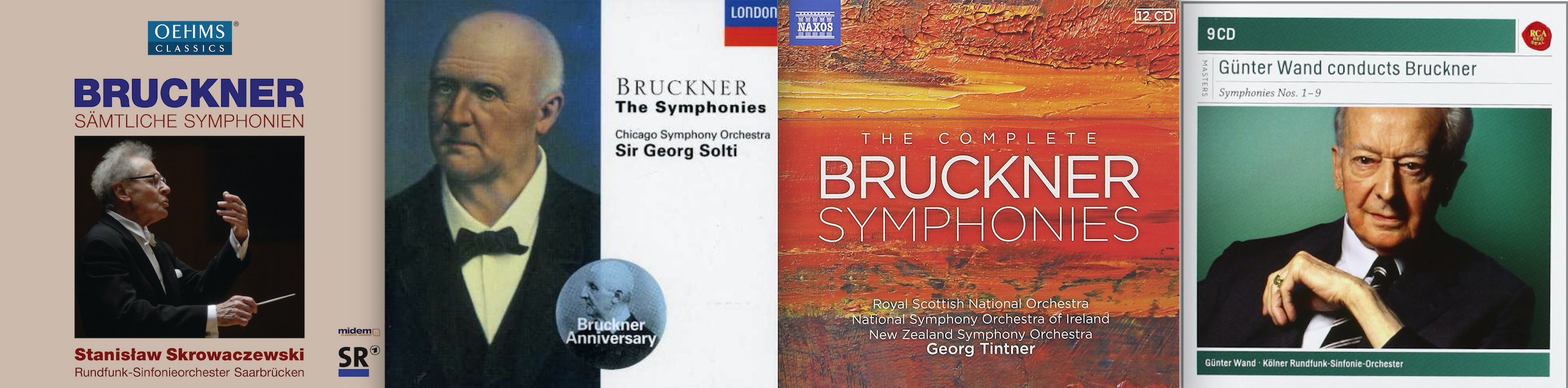

I recently discovered seven more box sets of Bruckner’s symphonies. I don’t know why I wasn’t aware of them before I started this blog. But, because of my Bruckner project, readers brought them to my attention. (Thank you…I think.)

Two of the box sets only have six of the nine Bruckner symphonies, which violates my rule (For my project, I chose box sets that were readily available that included all nine symphonies). But those two six-symphony sets are historically important enough for me to bend the rules. Just this once.

Therefore, when I’m done with this 144-day project, I’m going to create another site, and continue my Bruckner and Me project for another – are you ready for this: 57 more days – bringing the total number of days I’ll listen to Bruckner’s symphonies to 201. Nearly seven months of non-stop, daily, Bruckner. I will call the new site, unimaginatively enough, 57 More Days With Bruckner And Me.

It’s worth noting that this will beat my previous long-term project in which I listened to everything Mozart composed (see 180 Days With Mozart And Me, as well as the summary of my previous projects here).

I don’t believe anyone has ever undertaken a project of this magnitude (201 days!) before, particularly with Bruckner’s symphonies. My project might be the first.

But, I could be wrong. The hell do I know?

Anyway, on with the show!

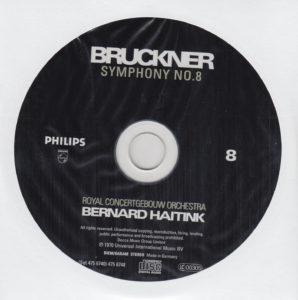

This morning’s conductor of Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 8 in C Minor (WAB 108) (nicknamed “The Apocalyptic,” although I don’t know why) is Dutch conductor Bernard Haitink (1929-).

This morning’s conductor of Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 8 in C Minor (WAB 108) (nicknamed “The Apocalyptic,” although I don’t know why) is Dutch conductor Bernard Haitink (1929-).

The orchestra is Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra.

I first encountered Maestro Haitink on Day 5 of my 144-day project. On that day, he interpreted Symphony No. 1.

Then again on Day 21, Symphony No. 2.

Then again on Day 37, Symphony No. 3.

Then again on Day 53, Symphony No. 4.

Then again on Day 69, Symphony No. 5.

Then again on Day 83, Symphony No. 6 – from the Bruckner Collection box set.

Then again on Day 85, Symphony No. 6 – from the Haitink box set.

Then, most recently, on Day 101, Symphony No. 7.

That’s a whole lotta Haitink going on.

Thankfully, I have been deeply impressed with Maestro Haitink. Whatever “it” is that makes a recording magical, his recordings usually have it.

But I’ll reserve the subjective stuff for later.

First, the objective aspects of this recording.

Bruckner’s Symphony No. 8 in C Minor (WAB 108), composed 1884-1890

Bruckner’s Symphony No. 8 in C Minor (WAB 108), composed 1884-1890

Bernard Haitink conducts

Haitink used the Haas edition, according to the CD booklet

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra plays

The symphony clocks in at 72.51

This was recorded in Amsterdam in June of 1960 (which makes it one of the oldest recordings)

Haitink was 31 when he conducted it (which makes him one of the youngest conductors)

Bruckner was 66 when he finished composing it

This recording was released on the Philips label

Bruckner wrote his symphonies in four parts. The time breakdown of this one (Symphony No. 8 in C Minor, Haas edition), from this particular conductor (Haitink) and this particular orchestra (Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra) is as follows:

I. Allegro moderato…………………………………………………………………………….13:57

II. Scherzo. Allegro moderato…………………………………………………………….13:33

II. Adagio. Feierlich langsam; aber nicht schleppend……………………….25:17

IV. Finale. Feierlich, nicht schnell……………………………………………………….20:44

Total running time: 72.51

The fine print at the bottom of the last page of the liner notes reads:

The recording of Symphonies Nos. 1-9 was based on the edition prepared by Robert Haas…

From its entry on Wikipedia,

Robert Haas published his edition of the Eighth Symphony in 1939. Haas mainly based his work on the 1890 autograph but also included some passages from the 1887 version that were changed or omitted in the 1890 score.

Haas argued that Levi’s comments were a crippling blow to Bruckner’s artistic confidence, even leading him to “entertain suicidal notions”, although Haas had no evidence for this. This led, Haas maintained, to Bruckner’s three-year effort to revise the Eighth Symphony and many of his earlier works. This line of thought supports Haas’ editorial methods. Haas took what he admired from Bruckner’s different versions and rolled them into his own version. He justified the rejection of various features of Bruckner’s 1890 revision on biographical grounds: they are the ideas of a Bruckner who mistrusted his own judgment, and therefore non-Brucknerian.

The most significant omissions that Bruckner made (and therefore of Haas’s restorations) are in the Adagio and Finale of the work. In addition, Haas inserted eight bars into the finale that he appears to have composed himself by combining the harmonies of the 1887 manuscript with material Bruckner penciled into the margin of the 1890 score, discarding five bars of Bruckner’s own music in the process. There were no footnotes or other indication in Haas’s edition that these changes had been made. Korstvedt has described these interventions as “exceed[ing] reasonable limits of scholarly responsibility”. Despite its dubious scholarship Haas’s edition has proved enduringly popular: conductors such as Herbert von Karajan, Bernard Haitink and Günter Wand continued to use it even after the Nowak/1890 edition was published, while noted Bruckner conductor Georg Tintner has written that the Haas edition is “the best” version of the symphony and referred to Haas himself as “brilliant”. On the other hand, Eugen Jochum used Haas’s edition for his first recording, made in 1949, before Nowak published his edition, and Nowak’s for his subsequent recordings, while Wilhelm Furtwängler, despite having given the premiere of the Haas score, reverted to the 1892 edition in his final years.

The controversy over the Haas edition centers on the fact that its musical text was a fabrication of the editor and was never approved by Bruckner himself.

The entire article on the Haas edition is worth reading. This is just a lengthy excerpt.

Now, the subjective aspects of today’s performance:

My Rating:

Recording quality: 5 (virtually flawless given that this is a 57-year-old recording)

Overall musicianship: 5

CD liner notes: 4 (essay translated into English, German, and French)

How does this make me feel: 5

A total “Huzzah!” performance!

This one had me gripped from start to finish – and thoroughly engrossed in the Scherzo and the Finale.

I’m amazed that this recording is 57 years old, and yet it sounds as fresh as if it were recorded 57 days ago. (NOTE: This is the third-oldest recording, following Eugen Jochum’s interpretation, recorded 1958, of Bruckner’s Fifth, on Day 70, and Franz Konwitschny’s interpretation, recorded 1951, of Bruckner’s Second, on Day 28).

What’s more, this performance is electrifying. It is magical, entertaining, moving, bold, emotional, and energetic.

This is one of my favorite recordings of all I’ve heard to date.

Highly recommended.

Triple “Huzzah!”

(Incidentally, now I remember what it is I heard on the local Classical radio station – WBLV – that first attracted me to Bruckner, via his Eighth. It was the Scherzo. As I’m listening to Haitink’s interpretation of the Scherzo, I’m recalling why I instantly fell in love with Bruckner. It wasn’t Haitink I heard that day in my car, however. That was, most likely, Karajan. Or Tennstedt. But this Haitink interpretation is bringing back the memories.)