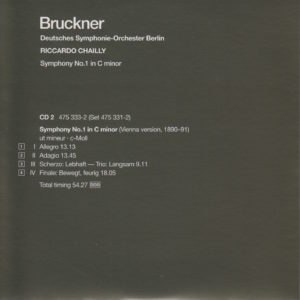

This morning’s conductor of Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 1 in C Minor (WAB 101) is Italian Riccardo Chailly (1953-). The orchestra is Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin.

This morning’s conductor of Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 1 in C Minor (WAB 101) is Italian Riccardo Chailly (1953-). The orchestra is Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin.

There is an important distinction between this version of Bruckner’s Symphony No. 1 and the one I heard yesterday. Barenboim used the Linz version. Chailly used the Vienna version.

So there are three variables this time: conductor, orchestra, and version.

So there are three variables this time: conductor, orchestra, and version.

First, let’s look at what’s objective: the run time for each of Bruckner’s four movements (all of Bruckner’s symphonies were written in the four-movement structure) in this particular composition (Symphony No. 1, the 1891 Vienna version), this particular conductor (Chailly) and this particular orchestra (Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin):

Allegro…………..13:13

Adagio……………13:45

Scherzo……………9:11

Finale……………..18:05

By way of comparison, here’s what the run time was for yesterday’s Barenboim version of Symphony No. 1:

Allegro…………..12:19

Adagio……………12:12

Scherzo……………9:06

Finale……………..13:28

Under Chailly’s direction, Allegro is nearly one minute longer…Adagio is a minute and a half longer…Scherzo is five seconds longer…And Finale is longer by nearly five full minutes.

What does that mean?

Two things are possible:

1. Chailly conducted this symphony at a slower tempo, and/or

2. The Vienna version of Symphony No. 1 is altered that much from the Linz version

Since I am not a musicologist or musician, I don’t know which of those is correct, if either is. All I can tell is that there’s a marked difference in how this symphony is presented compared to the Barenboim’s version yesterday.

As a reminder, here is what each term means (first two from the Wikipedia article):

Allegro = joyful; lively and fast. Moderately fast.

Adagio = ad agio, at ease. Slow, but not as slow as largo.

Scherzo = The word “scherzo,” meaning “I joke,” “I jest,” or “I play” in Italian, is a piece of music, often a movement from a larger piece such as a symphony or a sonata, often in 3/4 time. The precise definition has varied over the years, but scherzo often refers to a movement that replaces the minuet as the third movement in a four-movement work, such as a symphony, sonata, or string quartet. Scherzo also frequently refers to a fast-moving humorous composition that may or may not be part of a larger work.

Finale = the last movement of a sonata, symphony, or concerto; the ending of a piece of non-vocal classical music which has several movements; or, a prolonged final sequence at the end of an act of an opera or work of musical theatre.

The Vienna version of Symphony No. 1 was finished in 1890-91. Bruckner was 67. This recording of Chailly was made in 1988. Chailly was 35.

Okay, those are the objective stats.

Here are the subjective ones:

My Rating:

Recording quality: 3

Overall musicianship: 3

CD liner notes: 5

How does this make me feel: 2

To my ears, this recording lacks the depth and richness of Barenboim’s. It seems tinier, with less dynamic range.

Aside from Scherzo (Movement Three), which always catches my attention because it reminds me of the theme song to the TV series Agatha Christie’s Poirot (a resemblance I pointed out in a comment I posted to a blog I discovered called Miss Alexandrina Brant – check out her insights regarding the Poirot theme), I wasn’t gripped by any of this. I cannot explain why. But it left me cold. Or, at most, lukewarm.

How is that possible? It’s, ostensibly, the same piece of music, give or take. There’s only a run-time difference of, maybe, seven minutes.

Can there really be that much difference in the three variables of conductor, orchestra, and version?

I noticed something else about this recording: It’s labeled DDD, which means it’s an all-digital recording. That may make a difference, too. It would account for a bit of the tiny sound. Digital recordings, although crisp, can be too crisp.

From the excellent liner-notes essay by Andrew Huth:

Anton Bruckner was the most single-minded of composers. The very opposite of such artists as Beethoven, Berlioz or Stravinsky who were constantly transforming wide varieties of experience into their music, it is as though Bruckner spent all his life trying to express a single, big vision. In each of his symphonies he approaches this vision from different angles, inventing new techniques and structures to give it musical shape.

I found that brief introduction insightful and revealing. What it doesn’t answer, though, is “What was Bruckner’s ‘big vision’?”

The liner notes do reveal the profound impact composer Richard Wagner (1813-1883) had on Bruckner. I’ll explore that connection in later blog posts.

One more quote from Huth’s liner notes:

Most nineteenth-century composers were well-educated, articulate men who could explain their aims in conversation among friends or through writings for a broader public. Not Anton Bruckner. A shy and unassuming man, he lacked the intellectual weapons to explain or defend his music, and during his life and for many years afterwards it was subject to all manner of misunderstanding.

I find that sad, on many levels – not least of which is the question begged, “Why should Bruckner have to explain his music or defend his music at all?”

For whatever reason, this simple-minded man from Austria was able to compose music that astounds and delights to this day, a century and a half later. I don’t see any reason to be anything but grateful to Anton Bruckner for sharing his gift with us.