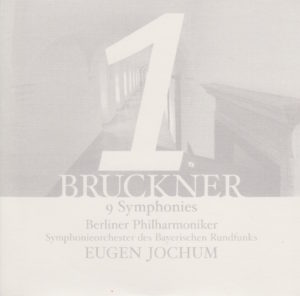

This morning’s conductor of Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 1 in C Minor (WAB 101) is German-born Eugen Jochum (1902-1987), unarguably one of the most highly respected interpreters of Anton Bruckner’s music who ever lived.

This morning’s conductor of Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 1 in C Minor (WAB 101) is German-born Eugen Jochum (1902-1987), unarguably one of the most highly respected interpreters of Anton Bruckner’s music who ever lived.

I have two CD box sets conducted by Jochum – this one, on the DG label, and one I’ll crack open tomorrow on the Warner Classics label. I chose to listen to the symphony from the DG set this morning because the recording is older. (I figured chronological order was a fair enough delineator.)

From the Wikipedia entry for Jochum:

From the Wikipedia entry for Jochum:

Jochum was born to a Roman Catholic family in Babenhausen, near Augsburg, Germany; his father was an organist and conductor. Jochum studied the piano and organ in Augsburg, enrolling in its Academy of Music from 1914 to 1922. He then studied at the Munich Conservatory, with his composition teacher being Hermann von Waltershausen; it was there that he changed his focus to conducting, his teacher being Siegmund von Hausegger, who conducted the first performance of the original version of the Ninth Symphony of Anton Bruckner and made the first recording of it.

Regarding his podium technique, Kenneth Woods blogs, “Look at his hands — very small and focused motions but so powerful.” Woods also states that “his sense of rubato, while still incredibly daring, is perhaps more un-erring than [that of] even Wilhelm Furtwängler.”

Jochum’s older brother Otto Jochum (1898–1969) was a composer and choral conductor; his younger brother Georg Ludwig Jochum (1909–1970) was, like Jochum, an orchestral conductor. His daughter Veronica Jochum is a pianist on the faculty of the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, Massachusetts.

Jochum died in Munich in 1987, at the age of 84. His wife Maria predeceased him, in 1985.

This particular recording represents another first for my 144-day journey. It was recorded in October of 1965 (51 years ago this month), which makes it the oldest symphony I’ve had the pleasure to experience since I started this project six days ago. That gives this an historic patina I’m going to have to take into account when I rate it. I don’t want the historicity of the recording to sway me. (Yet, I’m sure that’s part of why anyone would listen to this in the first place: it’s a historical recording from a renowned conductor and a revered orchestra. So ignore what I just typed.)

The orchestra is the Berliner Philharmoniker, one of the most prestigious in the world.

Despite the age of the recording, it is surprisingly vibrant and fresh. I can’t even detect much tape hiss. From time to time, if the volume in my earbuds is up high enough, I can hear a chair move or what sounds like somebody tapping (or bumping into) a music stand. In other words, the microphones were placed close enough to pick up ambient sounds, yet positioned far enough away to achieve an overall depth and clarity.

Jochum’s choice for Bruckner’s Symphony No. 1 in C Minor was the 1866 Linz version. Bruckner was 41 when he wrote Symphony No. 1. Jochum was 63 in this recording when he conducted it.

I noticed something about Movement II (Adagio) this morning: it sounds like a film score. It has very expressive, emotional moments and very bold, dynamic moments, but phrased in ways that sound like a film score from, say, composer John Williams. Or James Horner. Or Randy Newman. I swear in some of the Adagio (Movement II) or even Scherzo (Movement III) I hear reminiscent strains of Randy Newman’s score for the movie The Natural.

That lead me down a path of pondering…

I wonder if Bruckner’s symphonies resonate with me because they have a film-score sound to them. Despite having been written in the eighteenth century, they sound as though they were composed in the 21st – for a famous Hollywood movie, no less.

I think that may have something to do with it. Bruckner seems to compose for the mind as well as the heart. He paints grand, sweeping pictures that engage my head as well as my emotions.

Before I spend too much time pondering Bruckner’s appeal, let me get to the objective aspects of this recording, starting with the timing for each movement.

Bruckner wrote his symphonies in four parts. The breakdown of this one (1866 Linz version), from this particular conductor (Jochum) and this particular orchestra (Berliner Philharmoniker), is as follows:

Allegro…………..12:38

Adagio……………12:35

Scherzo……………8:55

Finale……………..13:13

The difference in time between Jochum and, say, Haitink is minimal. Here’s how Haitink’s performance of Symphony No. 1 played out yesterday:

Allegro…………..12:09

Adagio……………13:07

Scherzo……………8:51

Finale……………..12:47

As you (there’s that nebulous “you” again), the difference is a mere 91 seconds, a minute and a half.

Jochum stretches out Movement I (Allegro) a bit more, but truncates the second (Adagio). Both Jochum and Haitink keep Movement III (Scherzo) about the same (just :04 difference between the two). Jochum lengthens the fourth movement (Finale) by about a half minute.

But the overall difference between the two performances is minimal.

The CD booklet liner notes in the Jochum box are superb.

They include two essays, one written by Constantin Floros, and the second written by none other than conductor Eugen Jochum himself. What greater insight could we have than to hear from the conductor?

First, a brief quote from the Floros essay, titled “The Development of Bruckner’s Symphonic Style”:

Anton Bruckner’s First Symphony must, from a historical point of view, be acknowledged to possess a high degree of originality and daring, even if we take into account the fact that it had been preceded by the composition of both the so-called Study Symphony in F minor, and the draft of the Symphony in D minor, known as “No. 0” (although the latter was not completed until 1869).

The First Symphony displays almost all the prominent characteristics of Bruckner’s personal style: the powerful climactic surges which go a long way to determining formal articulation, especially in the outer movements; the significance of the number three; the suitability of his initial themes for further development; the elemental rhythmic energy of the G minor Scherzo; the fondness for a densely polyphonic style; the idiosyncratic instrumentation; the individual relationship between diatonicism and chromaticism.

Now, from Jochum’s essay, titled “The Interpretation of Bruckner’s Symphonies”:

As a general rule, however, I must caution against subjecting Bruckner to the excessive accelerandi [speeding up] and ritardandi [gradually slowing down] that the sensual music of the late Romantic era demands. Bruckner’s music develops out of an “eternal rest in the God the Lord” and a mystical relationship to God which is matched by one other composer in the whole history of modern European music, and then in a quite different form: in J.S. Bach.

So far as orchestration goes, Bruckner scarcely deserves the name of a Romantic…the span of his ideas reaches, however, from the mysticism of the early Gothic Middle Ages, through the world of Palestrina, to the 19th century with its closeness to nature…

Bruckner…is filled instead with the warmth and vitality of the landscape and the native folk culture of Austria. Behind that, however, as the background to all his music, lie a piety and a mystical personal relationship to God known otherwise in European music only to Bach.

That was one of the most revealing insights into Bruckner I have ever read. I had no idea. Maybe my connection to Bruckner is via the composer’s mysticism? That’s an area in which I’ve dwelled of late.

Okay. Now, with all of that at the forefront of my mind, let’s turn to the subjective aspects to this recording.

My Rating:

Recording quality: 4 (only slight tape hiss and ambient sounds audible)

Overall musicianship: 5

CD liner notes: 5 (includes two superb essays, one by Jochum)

How does this make me feel: 4

This is an exceptional performance of Symphony No. 1. It is filled with a palpable reverence, but lacking what could have been a concomitant distance, rather than a loving intimacy. The recording is warm. The brass instruments are not harsh. Lots of depth here.

Why only a “4” on feeling?

I dunno.

Despite Jochum’s obvious reverence for the subject matter, I don’t get the “wow factor” with this performance. I can hear it’s splendid. I fully understand its historical significance. But I wasn’t instantly drawn in the way I was by, say, Haitink or Schaller.

If the rest of these Jochum symphonies are as exceptional as this one, I can easily see how this box set would be one I’d recommend to others. So far, it’s wonderful.