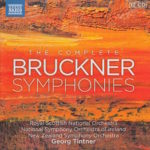

This morning’s conductor of Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 1 in C Minor (WAB 101) is one I’ve been eagerly awaiting: Georg Tintner (1917-1999), the Austrian-born composer/conductor that I first heard on a local Classical radio station.

This morning’s conductor of Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 1 in C Minor (WAB 101) is one I’ve been eagerly awaiting: Georg Tintner (1917-1999), the Austrian-born composer/conductor that I first heard on a local Classical radio station.

It was Bruckner’s Symphony No. 8. I remember immediately being deeply moved by Bruckner’s symphony and going home to look them up on Amazon. I bought the Karajan (DG label) version first. A couple of weeks later, I bought the Tintner (EMI label) version. I’m not sure why I bought both. Maybe I heard the station play, over the course of a few weeks, recordings from both. Or maybe I scrambled over to Amazon, saw the director the station played (probably Karajan) and bought it…but then later saw a Tintner edition at a reasonable price on a different label and decided to compare them.

Don’t remember now. All I remember is this: I knew a few conductor names going into this Buckner project. Georg Tintner was one of them.

From his entry on Wikipedia:

Georg Tintner, CM (22 May 1917 – 2 October 1999) was an Austrian-born conductor whose career was principally in New Zealand, Australia, and Canada. Although best known as a conductor, he was also a composer (he considered himself a composer who conducted).

As a child he was a singer in the Vienna Boys’ Choir, directed by Franz Schalk. At the Vienna State Academy he studied composition with Joseph Marx and conducting with Felix Weingartner. Soon he was assistant conductor of the Vienna Volksoper.

Due to the persecution of Jews, Tintner moved out of Vienna in 1938, arriving in Auckland, New Zealand in 1940. En route, he was falsely accused of being a German spy and got arrested in Australia. He conducted a church choir until after the war, when he took over the Auckland Choral Society in 1947, and the Auckland String Players in 1948. He became a New Zealand citizen in 1946. In 1954, he went to Australia and became resident conductor of the National Opera of Australia (a private company) before joining the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust Opera in 1957. Tintner is credited with pioneering televised opera in Australia.

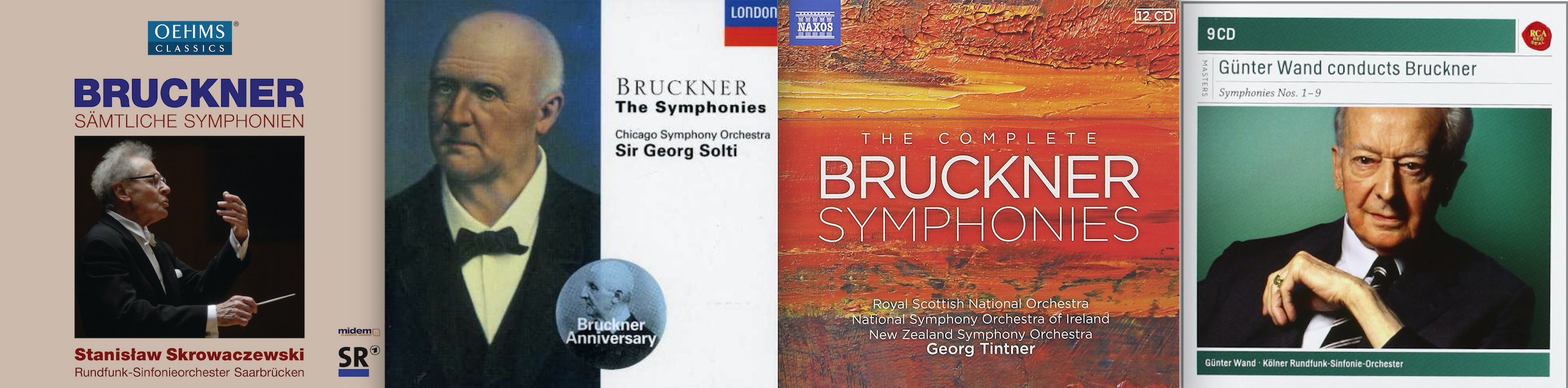

Tintner was described as “one of the greatest living Bruckner conductors.” He recorded a much-praised complete cycle of Bruckner symphonies for the Naxos CD label shortly before the end of his life (recording sessions: 1995-98). In addition to the eleven symphonies this cycle includes the 1876 Adagio and the 1878 ‘Volkfest Finale’.

I’m especially interested in that last paragraph, one to which I wholeheartedly agree.

But, before I get too subjective, I’ll run through a few of the objective stats/facts about this morning’s recording.

But, before I get too subjective, I’ll run through a few of the objective stats/facts about this morning’s recording.

First of all, I have not yet seen – in 15 box sets – this information: “Original 1866 Unrevised Linz Version.”

Apparently, Tintner used the actual first version Bruckner wrote, with no subsequent revisions. That leads me to believe I’d better go back and pay more attention to the versions used by each of these conductors. Perhaps the subsequent editing played a role in how these symphonies sounded to me. So, for example, even though most used the Linz version, did they use – as did Tintner – the original, unedited Linz version? Or did they use the Linz version plus edits? And did that account for time differences or even tonal differences?

Hmmm. How deep do I want to tumble down this rabbit hole?

Well, since I’m already about half-way down, I guess I’d better go back and do it right.

I also have not read anything like this in previous liner notes: “NOTE: in the recordings in this series the second violins are placed on the right of the conductor, for the antiphonal effect between first and second violins that Bruckner expected to hear.”

(Antiphony is the “call and response” style that I enjoy a lot in music.)

So far, I’m getting the impression that this box set and this cycle of Bruckner symphonies from Georg Tintner is as authentic – and reverently created – as it gets.

According to the back of the CD jacket, this recording was made “at Henry Wood Hall, Glasgow, on 31st August and 1st September 1998.”

Tintner died a little over a year later, in 1999. He was 81 when he conducted this recording of Bruckner’s First Symphony.

The orchestra on this recording is the Royal Scottish National Orchestra. Here is their official web site.

According to The New York Times review (written by LAWRENCE B. JOHNSON on NOV. 29, 1998) of this box set, this is “A Thinking Mans’s Bruckner”:

He has devoted himself to Bruckner for many years, and his expertise tells, not only in the originality of the present interpretations but also in his accompanying essays. Although Bruckner often revised, even truncated, his symphonies at the urging of colleagues, Mr. Tintner is a strong advocate of playing the first published versions, as he does here.

The extensive liner notes were written by Georg Tintner, and they are among the most insightful and engaging I have ever read. Without doubt, Tintner knew his Bruckner – inside and out.

From an article in The Telegraph (UK) after Tintner’s death in 1999,

Tintner was one of those all-too-common victims of 20th-century prejudice, an artist who had to attain a venerable age before anyone was prepared to acknowledge his unarguable gifts. Vindication came too late to repair the damage. Both the manner of Tintner’s death – a suicide leap from his 11th-floor apartment in Halifax, Nova Scotia – and the causes of his neglect cry out for some serious soul-searching (assuming the music world has a soul worth searching).

Tintner cut, admittedly, a slightly quaint figure. A strict vegan, he walked around with a jamjar full of bean sprouts that constituted his lunch.

So, he was “a strict vegan.” And he committed suicide.

So, he was “a strict vegan.” And he committed suicide.

And he was, by all accounts so far, a precise interpreter of Bruckner’s music.

I’m looking forward to reading the book about Tintner’s life Out of Time: The Vexed Life Of Georg Tintner, written by his widow Tanya Buchdahl Tintner.

Here’s a very fine online bio (Georg Tintner: The Gift of Being Simple”) of Georg Tintner written by Peter Gutmann.

Okay. Enough of that. Time for the nuts and bolts.

Bruckner wrote his symphonies in four parts. The time breakdown of this one (original Linz version, 1866, unedited), from this particular conductor (Tintner) and this particular orchestra (Royal Scottish National Orchestra) is as follows:

Allegro…………..14:39

Adagio……………15:22

Scherzo……………9:07

Finale……………..15:55

I’ll compare Tintner’s interpretation to one from one of my favorite conductors so far: Jochum, from my post on 9 October 2016.

The timing breakdown from the Jochum interpretation (which also used the Linz version, albeit not the original, unedited 1866 version – as far as I know) with orchestral performance by Staatskapelle Dresden was:

Allegro…………..12:29

Adagio……………12:38

Scherzo……………9:02

Finale……………..12:57

As you can see, the Tintner version is longer by some 7-8 minutes.

Now, here is the subjective aspect:

My Rating:

Recording quality: 5

Overall musicianship: 5

CD liner notes: 5 (extensive essays about Bruckner and his symphonies written by Georg Tintner)

How does this make me feel: 5

I’m not sure the last one (“How does this make me feel?”) is not influenced mightily by everything I’ve read about this box and about Georg Tintner’s life. Knowing how committed he was to the spirit of Bruckner, right down to choosing the unedited, unrevised original 1866 Linz version and then arranging his orchestra’s violin section to be an accurate representation of how Bruckner himself expected to hear the music probably pushed this recording from a 4 to a 5.

To my eyes and ears, this is the perfect Bruckner box set. It is well constructed. It is thorough. It is meticulously recorded.

Even though this interpretation by Tintner exceeds the timing of that by Jochum, it doesn’t feel bloated or ponderous as it did when I listened to the “sluggish” Maazel interpretation.

This Tintner recording is the gold standard so far – at least, for the First Symphony. We’ll see if the rest of Bruckner’s symphonies, under Tintner’s hand, hold up to this one.