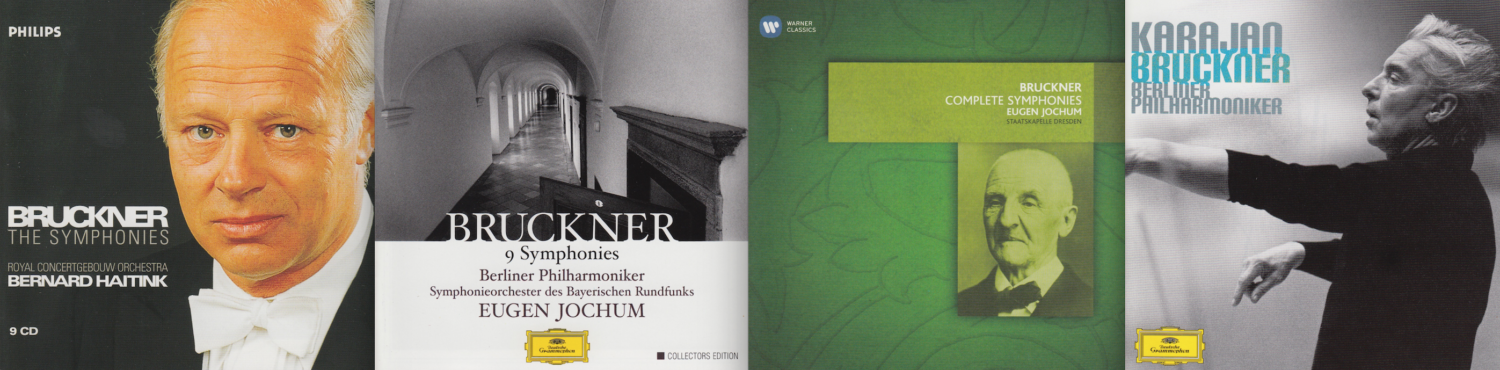

This morning begins a new chapter. Today, I start the next 16-day leg of my journey – this time, listening to Bruckner’s Symphony No. 2 in C Minor (WAB 102) from the perspective of 15 different conductors (Eugen Jochum conducts each symphony twice; in two different box sets).

This morning begins a new chapter. Today, I start the next 16-day leg of my journey – this time, listening to Bruckner’s Symphony No. 2 in C Minor (WAB 102) from the perspective of 15 different conductors (Eugen Jochum conducts each symphony twice; in two different box sets).

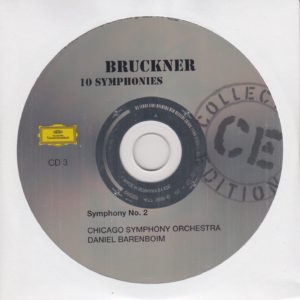

This morning’s conductor of Anton Bruckner’s Second Symphony is one of my favorites so far – Argentine-born pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim (1942-). You can read what I wrote about my first encounter with Barenboim here.

Barenboim set the bar high with his interpretation of Bruckner’s First Symphony. I’m eager to hear what he does with his Second.

Barenboim set the bar high with his interpretation of Bruckner’s First Symphony. I’m eager to hear what he does with his Second.

In both cases, this is the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. This performance was recorded in 1981. Barenboim was 39. Bruckner was 53 when he published Symphony No. 2 in C Minor in 1877. This CD set is on the DG (Deutsche Grammophon) Record Label.

As I listen to the Second Symphony, I’m going to read about it, starting with what’s in the liner notes to the Barenboim CD set:

According to Chilean Bruckner scholar Juan Cahis, Symphony No. 2 in C Minor is available in two versions. The first version was composed in 1872. The second version is a result of editing in 1875-1877. The version Daniel Barneboim and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra are using in this recording is the 1877, or second, version.

That’s about all I can glean from these liner notes. Even though the booklet is 25 pages long, it’s just one broad overview essay titled “Nine in number, eighteen in total” translated into English, German, and French.

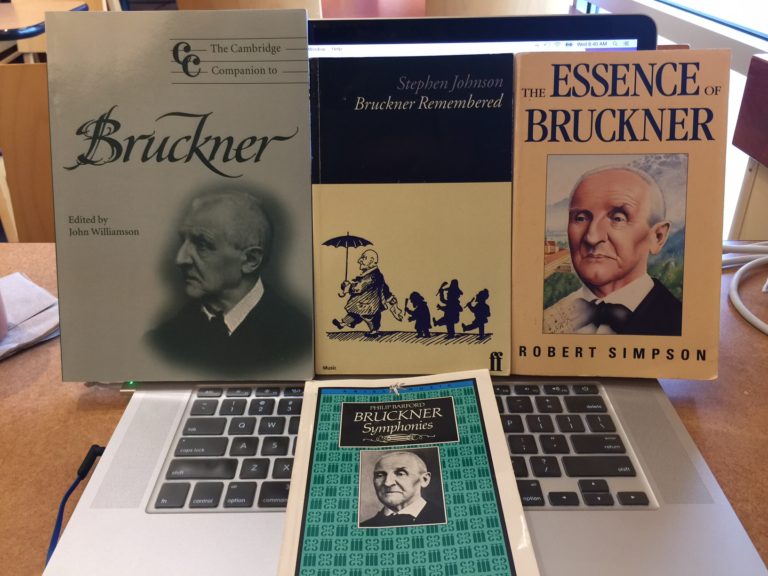

For more in-depth information on each particular symphony, I have to consult one (or more) of the four hard-to-find Bruckner books I purchased.

From Philip Barford’s fine little book Bruckner Symphonies (published 1978):

We may often wonder at the psychological burden of genius, at the reaction of human personality to the inward pressure of works yet unborn. After completing the First Symphony, Bruckner suffered a nervous breakdown, the contributory causes of which may well have originated in a recurring lack of self-confidence.

The mysticism of this word does not, like Beethoven’s, place it outside the limits of Christian orthodoxy. Buckner’s Mass is Roman Catholic church music, testifying to the conviction of a man whose religious needs were wholly served by the Church.

Both Haas and Nowak used the 1877 version of the Second Symphony in preparing their editions.

From the superb book The Essence of Bruckner, by Robert Simpson (first published 1967, revised 1992):

The Second Symphony was begun in Long in 1871. Bruckner went there to play the organ, and his success prompted him to the remark, ‘In England my music is really understood.’ Not that any of his compositions had ever been heard there, but his powers of extemporization must have been impressive. It is ironic to think of the blank reception that England gave his symphonies for so many years, until the 1850s, in fact.

Simpson writes at length of the different versions of the Second Symphony, and the challenges of knowing which version to use, or what cuts to make or restore. (Something I’ll have to explore a bit when I get more time.) He concludes with:

To perceive the spaces Bruckner wanted to fill satisfactorily is better than to have a work that is too long for the space we would like it to fill. Haas was right. The dropped passages (except perhaps one) should be restored, as I hope now to demonstrate as we explore the symphony.

After all this harping on inequalities in No. 2, it is necessary to describe it as a most beautiful symphony, too little known.

A brief mention about musicologist Robert Haas, editor of Bruckner’s symphonies. From his entry on Wikipedia:

Robert Maria Haas (1886-1960) Austrian musicologist.

At the beginning of his career with the Austrian national library, Haas was mostly interested in Baroque and Classical music. Later on, he was engaged by the newly formed International Bruckner Society to work on a complete edition of Anton Bruckner’s Symphonies and Masses based on the original manuscripts bequeathed by the composer to the Vienna library.

Haas’s editions of Bruckner are controversial. Scholar Benjamin Korstvedt charges that in the Second, Eighth and Seventh symphonies Haas made changes to Bruckner’s musical texts that “went beyond the limits of scholarly responsibility”.

Another source of controversy is Haas’s attachment to the Nazi party. Haas was a member of the Nazi party and did not hesitate to use the language of Naziism to garner approval for his work. He portrayed Bruckner as being a pure and simple country soul who had been corrupted by “cosmopolitan” and Jewish forces. This proved Haas’s undoing…

On the other hand, noted Bruckner conductor Georg Tintner has described Haas as “brilliant” and calls Haas’s edition of Bruckner’s Eighth Symphony “the best” of all available versions. Many conductors, including Herbert von Karajan, Bernard Haitink, Daniel Barenboim, Takashi Asahina and Günter Wand continued to prefer Haas’s editions, even after the more scholarly Nowak editions became available.

To quote Mr. Spock: “Fascinating.”

Another name associated with Bruckner’s symphonies (from an editorial point of view) is that of Leopold Nowak. According to his entry on Wikipedia:

Leopold Nowak (1904-1991) was a musicologist chiefly known for editing the works by Anton Bruckner for the International Bruckner Society. He reconstructed the original form of some of those works, most of which had been revised and edited many times.

Nowak was born in Vienna, Austria. He studied piano and organ at the Imperial Academy of Music in Vienna. He studied musicology with Guido Adler and Robert Lach at the Vienna University, where he later taught from 1932 to 1973.

He succeeded Robert Haas as music director of the music collection of the Austrian National Library in 1946, and is credited with helping preserve documents about Bruckner.

Okay, that’s what’s going on with the versions of Bruckner’s works.

Bruckner wrote his symphonies in four parts. The time breakdown of this one (Symphony No. 2 in C Minor, 1877 version), from this particular conductor (Barenboim) and this particular orchestra (Chicago Symphony Orchestra) is as follows:

Allegro……………19:13

Adagio……………17:10

Scherzo………….10:21

Finale……………..19:33

Now here’s my subjective opinion on the Second Symphony:

My Rating:

Recording quality: 4

Overall musicianship: 5

CD liner notes: 4 (short essay in three languages)

How does this make me feel: 3

This is a long piece of music, over an hour in length. The four movements are not as dynamic as those of the First Symphony. Therefore, listening requires much more attentiveness to hear the subtleties.

One movement (I forgot which one now) features one of my favorite sounds in an orchestra: Pizzicato, which is a style of playing in which stringed instruments are plucked.

The end of Movement II (Adagio) sounds similar to the end of Movement II in Symphony No. 1. It tapers off sweetly and as if sending notes upward to heaven.

Movement III (Scherzo) bursts onto the scene with drama and bombast. But it quickly settles down into something less catchy as the Scherzo from Symphony No. 1.

Overall, I agree with author Simpson that this is “a most beautiful symphony.” It is pleasant and would make for terrific background music.

I can see right now, though, that some of the conductors to whom I’ve listened so far could make Symphony No. 2 a tough slog for me if they do what they did with Symphony No. 1.

Lets hope not.