This morning begins a new chapter.

This morning begins a new chapter.

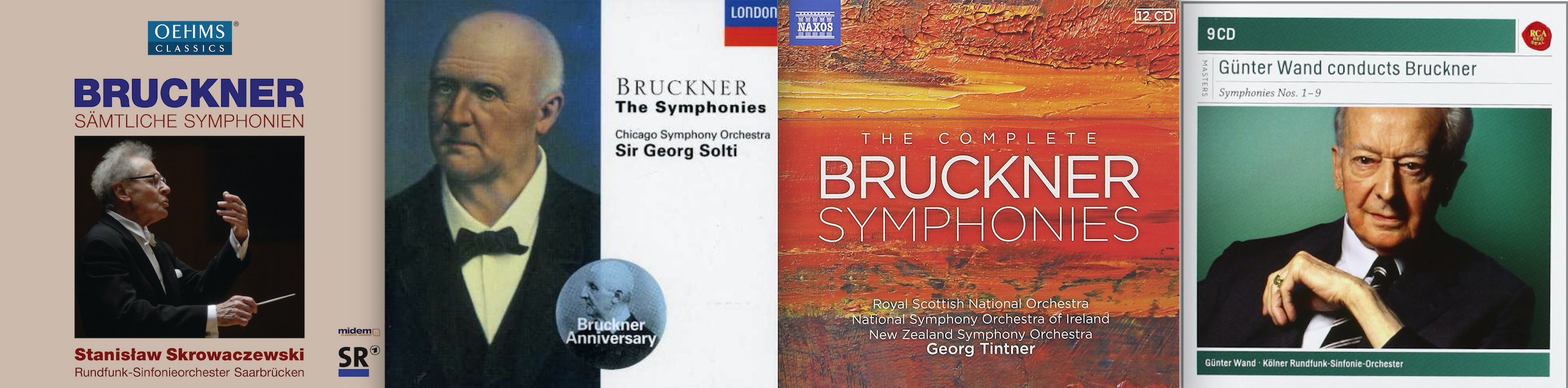

Today, I start the next 16-day leg of my 144-day journey – this time, listening to Bruckner’s Symphony No. 3 in D Minor (WAB 103), nicknamed “Wagner,” from the perspective of 15 different conductors (Eugen Jochum conducts each symphony twice; in two different box sets).

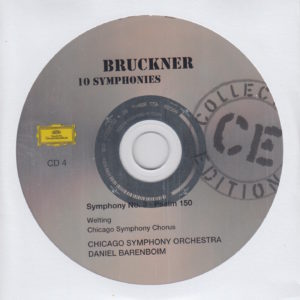

This morning’s conductor of Anton Bruckner’s Third Symphony is one of my favorites so far – Argentine-born pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim (1942-). You can read what I wrote about my first encounter (Day 1) with Barenboim here, and my second encounter with Barenboim (Day 17) here.

Barenboim set the bar high with his interpretations of Bruckner’s First Symphony and Second Symphony. I’m eager to hear what he does with his Third Symphony.

Barenboim set the bar high with his interpretations of Bruckner’s First Symphony and Second Symphony. I’m eager to hear what he does with his Third Symphony.

First of all, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that D Minor, according to Spinal Tap’s Nigel Tufnel, is “the saddest of all keys.”

So, I’m prepared to “weep instantly” when I hear Bruckner’s Third Symphony.

I’m not, of course.

However, from what I’ve been reading about its reception among critics, apparently others did.

According to the book Bruckner Symphonies by Philip Barford (pages 31-33),

According to the book Bruckner Symphonies by Philip Barford (pages 31-33),

Eduard Hanslick wrote of the Third Symphony that it defied understanding, that its poetic meaning was never revealed, and that its principle of contiuity was elusive and made it difficult to grasp. In his criticism, printed in the Wiener Zeitung on 16 December 1877, he accused Bruckner of confusing Beethoven with Wagner and finally submitting to Wagnerian influence.

To Hanslick, “the essence of music is sound in motion”…Hanslick championed Brahms, the supposed true heir of Beethoven, against Wagner and his conception of Gesamtkunstwerk, which put forward a passionate plea for the synthesis of all the arts with philosophy, and thus led to a symbolic interpretation of music…thus the art and theory of Tonsatz, the structure of sound in motion, becomes a musical vehicle of the flux of the inner life.

What about Bruckner? Bruckner brought down calamity upon his own head. Entranced by the sound of Wagner’s music, whilst remaining wholly indifferent to the theory of Gesamtkunstwerk, he dedicated the Third Symphony to him without the remotest idea what adverse consequences would follow. Wagner accepted the dedication, and always referred to the symphony afterwards as the one with the trumpet, on account of the powerful opening theme, which strongly appealed to him.

And there it is!

Gesamtkunstwerk.

This is one of the things I love about doing these “…And Me” music projects. The discoveries I make excite me. I had never heard of Gesamtkunstwerk before. So I chased down the word, read up on, as well as Wagner’s book Art and Revolution, and am having a delightful sidetracked morning.

Discovering new words, instruments, concepts, periods of history, authors, composers, etc., is why I do this.

So I’m thrilled to learn about Gesamtkunstwerk.

Anyway, back to our regularly scheduled program…

According to its entry on Wikipedia,

Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 3 in D minor, WAB 103, was dedicated to Richard Wagner and is sometimes known as his “Wagner Symphony”. It was written in 1873, revised in 1877 and again in 1889.

The work has been characterised as “difficult”, and is regarded by some as Bruckner’s artistic breakthrough. According to Rudolf Kloiber, the third symphony “opens the sequence of Bruckner’s masterpieces, in which his creativity meets monumental ability of symphonic construction.” The work is notorious as the most-revised of Bruckner’s symphonies, and there exist no fewer than six versions, with three of them, the 1873 original version, the 1877-78 version, and the composer’s last thoughts of 1889, being widely performed today.

According to the book The Essence of Bruckner, by Robert Simpson (p. 64),

According to the book The Essence of Bruckner, by Robert Simpson (p. 64),

…it is now clear to me that the revisions of the Third Symphony in 1877/8 and 1889/90 and the first revision of the Fourth (not available until 1978) show that Bruckner did not know what he had achieved in the 1873/4 version of No. 3, the score that Wagner accepted with justifiable enthusiasm. The well-meaning but often disastrous attentions of his friends and his own inability to resist them produce nothing but confusion…

It can be argued with some certainty that Bruckner felt his objectives instinctively, unable to define them or perhaps even understand them himself.

I wonder if this aspect of Bruckner’s style of work adds to the mystique, enhances his greatness, or if Bruckner’s seeming lack of confidence and constant revisions detract from our ability to appreciate his music?

I don’t know enough to know what to think about that. My immediate guess is that all of these revisions, some of which are inferior, prevent us from knowing exactly what Bruckner was thinking – and even less about what he wanted us to play over a century later. But maybe part of the fun of Bruckner is discovering new things about his works.

The hell do I know?

It’s time to dive into the nuts and bolts of this morning’s recording:

Bruckner’s Symphony No. 3 in D Minor, composed in 1873

The version used is the 1877 version

Daniel Barenboim conducts

Chicago Symphony Orchestra plays

The symphony clocks in at 69:18

This was recorded in December, 1980, in Chicago, Illinois

Barenboim was 38 when he conducted it

Bruckner was 49 when he composed it

This recording was released on the Deutsche Grammophon Record Label

Bruckner wrote his symphonies in four parts. The time breakdown of this one (Symphony No. 3 in D Minor, 1877 version), from this particular conductor (Barenboim) and this particular orchestra (Chicago Symphony Orchestra) is as follows:

Moderato (Gemäßigt, mehr bewegt, misterioso, officially)………….19:07

Adagio (Bewegt, quasi Andante, officially)…………………………………….15:42

Scherzo…………………………………………………………………………………………….7:22

Finale………………………………………………………………………………………………15:24

Total: 69:18

All diversions, distractions, and serendipity aside, let’s turn to the subjective aspects of this morning’s recording.

My Rating:

Recording quality: 4

Overall musicianship: 5

CD liner notes: 4 (fine, albeit brief, essays)

How does this make me feel: 3

I’m not sure what to make of Bruckner’s Third Symphony – at least, in the hands of Barenboimm and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

The first two times I listened to it, nothing grabbed me. Nothing jumped out and excited me, as it did with his previous two symphonies. This one is more inscrutable. Enigmatic. Impenetrable.

Rather than hearing certain themes/melodies/pairings of instruments, I’m hearing it as a whole.

Do you know what I mean? It’s entering my brain as one big thing, a whole – rather than a sum of parts.

It’s like a pop song without the hook. There’s little here for my brain to grab onto and remember. No ear worms.

Although…

The opening bars of Scherzo (Third Movement) are stirring, and the Finale (Fourth Movement) gets my blood pumping.

But, again, it’s not like there are certain melodic passages to which I can point. (There is a bit of pizzicato in the Finale, around the 8:34 mark. I don’t know what it is; I’m a sucker for pizzicato.)

All in all, so far – granted, I’ve only heard one conductor and one orchestra – the Third Symphony is my least favorite. Of course, it’s entirely possible that all the farting around I did this morning – all the serendipity, the rabbit holes, the researching of tangential information – kept me from fully appreciating Symphony No. 3 in D Minor because I wasn’t actually paying attention to it.

I’m sure by the end of this 16-day leg I’ll have grown accustomed to its face, so to speak.

Either that, or I’ll be truly good and sick of it.