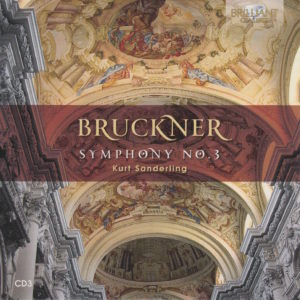

This morning’s conductor of Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 3 in D Minor (WAB 103), nicknamed “Wagner,” is German-born Kurt Sanderling (1912-2011), another person about whom I knew nothing and of whom I had never heard until I started this project.

This morning’s conductor of Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 3 in D Minor (WAB 103), nicknamed “Wagner,” is German-born Kurt Sanderling (1912-2011), another person about whom I knew nothing and of whom I had never heard until I started this project.

This is the first time I’ve listened Conductor Sanderling. So there is no frame of reference for this performance. I am hearing it based on its own merit.

I can say this, though: I am listening to Mr. Sanderling this morning because he was in the Bruckner box prominently titled Heinz Rogner, from which I discovered (on Day 28) Franz Konwitschny and, (on Day 12) Vaclav Neumann.

The first time I opened the Bruckner Complete Symphonies box, I thought the conductor was going to be Heinz Rogner. But who can blame me? The largest name on the cover of the box set is Heinz Rogner. So, naturally, I positioned this CD after yesterday’s Paternostro performance (R comes after P, you see). However, now it appears this box set – released by the extraordinary Brilliant Classics label – only listed Heinz Rogner’s name larger than the others, giving the impression that it was a Heinz Rogner-conducted series of Bruckner symphonies. (See below.)

As it turns out, Sanderling happens to come after Paternostro and before Skrowaczewski, anyway. So the appearance of Sanderling’s name in this listening order probably went unnoticed.

For the same reason why I positioned the Bruckner Collection box set under “C” in the listening order – even though the set contains recordings from various conductors – I can leave this one right here, regardless who conducts. The box set states its main conductor is Heinz Rogner. So the set stays in the “R” section. And “R” follows “P” no matter how you slice it.

For the same reason why I positioned the Bruckner Collection box set under “C” in the listening order – even though the set contains recordings from various conductors – I can leave this one right here, regardless who conducts. The box set states its main conductor is Heinz Rogner. So the set stays in the “R” section. And “R” follows “P” no matter how you slice it.

Brilliant Classics is my favorite label for Classical music at a terrific value. Most of what I have in my collection – all the box sets, anyway – are from Brilliant Classics. Brilliant releases very high-quality music at the most reasonable prices I’ve ever seen.

Okay. Enough with the subjective. I need to do some ‘sploring to learn two things, primarily: (1) Who Mr. Sanderling is/was, and (2) to learn who the editor is/was for the 1890 version used by Mr. Sanderling. On the CD sleeve it reads, “ed. Raettig.”

But who’s “Raettig”? That’s not a name I’ve encountered before.

So, I’m off to let my fingers do the Googling.

According to the UK Telegraph, which posted this obituary on Mr. Sanderling:

Kurt Sanderling, who has died aged 98, was a connoisseurs’ conductor, highly regarded for his interpretations of Beethoven and Shostakovich.

Forced out of Germany by the Nazis, he made his career in Russia until, in 1960, he returned to what was then East Germany. He did not work extensively in the West until the 1970s, when orchestras were deeply impressed by his combination of clarity and dramatic force. They found him to be an old-school disciplinarian, but above all a musician of modesty and integrity.

And this obituary, from the UK Independent:

Kurt Sanderling: Conductor widely regarded as one of the greatest of the 20th century

Kurt Sanderling was one of the great conductors of the 20th century, a last living link with the era of the podium giants, a man whose personal modesty was matched by immense musical authority. You came away from a Sanderling concert having had music you thought you knew revealed in its true nature, it seemed, for the first time.

I can’t believe I’ve never heard of Mr. Sanderling. Makes me sad.

But I’m glad I’m hearing him now. (And enjoying it, too – but I’m not supposed to reveal that yet.)

I’m still digging for information on Theodor Raettig, the editor of this particular (1890) of version of Bruckner’s Third Symphony, which is described in the box set’s liner notes (written by Philipp Adlung) this way:

Symphony No. 3: Such is life

Long recognized as a staple of the symphonic repertory, Bruckner’s Third Symphony in D minor is the first among his eleven symphonic essays (of which he regarded nine as worthy of inclusions in the canon) to provide incontestable evidence of his consummate artistry.Bruckner’s Symphony in D minor, written in the key originally chosen for his actual second, the so-called Symphony No. ), was greatly influenced by Beethoven’s Ninth, as the opening bars suggest.

Interesting. Here are the nuts and bolts (the objective aspects) of this morning’s listening experience:

Bruckner’s Symphony No. 3 in D Minor, composed in 1873

Kurt Sanderling conducts

The version Sanderling used is the 1890 version, ed. Raettig

Gewandhausorchester Leipzig plays

The symphony clocks in at 64:00 (second longest I’ve heard so far)

This was recorded in June of 1963 in Leipzig, Germany

Sanderling was 51 when he conducted it

Bruckner was 49 when he composed it

This recording was released on the Brilliant Classics record label

Bruckner wrote his symphonies in four parts. The time breakdown of this one (Symphony No. 3 in D Minor, 1890 version), from this particular conductor (Sanderling) and this particular orchestra (Gewandhausorchester Leipzig) is as follows:

Moderato (Sehr bewegt, officially)………………………….23:05

Adagio (etwas ewegt, quasi Andante, officially)……..17:28

Scherzo: Ziemlich schnell………………………………………….7:39

Finale: Allegro…………………………………………………………..15:28

Total: 64:00

Okay. Now for the subjective stuff…

My Rating:

Recording quality: 3 (clear, but a bit flat; lacks depth)

Overall musicianship: 4

CD liner notes: 3 (extensive essays on Bruckner’s symphonies; but no information about the conductors and orchestras)

How does this make me feel: 5

Whatever it is that draws me into a recording, this has. I was hooked from the opening notes of Movement I.

By the end of the Finale (Movement IV) I was sufficiently shaken and stirred, ready to jump to my feet and shout “Huzzah!” And “Encore!”

Aside from this recording not having the depth of others I’ve heard (it may be a mono recording, for all I know), it’s still a very powerful performance.

The pizzicato of Movement I caught my attention.

Ditto for the French horn (around the 7:40 mark) and the beautiful, delicate climax to Movement II.

And I was totally stirred by the drama and power of Movement III.

And, as I wrote, the Finale brought me to my feet.

I haven’t encountered anything released by Brilliant Classics that wasn’t first-rate. This is no exception. The recording may be 53 years old, but this is a terrific performance to keep and release today. It’s a gem.

Which, now that I realize it, is the logo for Brilliant Classics.

NOTE: In the book The Essence of Bruckner by Robert Simpson, Theodor Raettig is spelled Theodor Rattig, and he is referred to on page 66 as the “publisher” of Bruckner’s Third Symphony. I wonder if that’s why I can’t find anything about him online? I was Googling an incorrect (or alternate) spelling.

Ahh…

In the book Bruckner Remembered, by Stephen Johnson, there is this on page 115:

Theodor Rattig was the proprietor of the Bosendorfer publishing house, Bussjager & Rattig. His offer to publish the Third Symphony was, as he says, a timely gesture. Rattig published the orchestral score and a four-hand piano arrangement by Rudolf Kryzyzanowski and the seventeen-year-old Gustav Mahler, who had also attended the performance in the Musikverein and, like, Rattig, and been deeply impressed by what he heard.

Okay, then. There you have it.

The spelling on the Brilliant Classics CD sleeve is likely incorrect. A typo of sorts.

But now I know who Theodor Rattig was.